Untitled (Production Still), 1982. Inkjet print on Hahnemühle paper, 10 5/8 × 7 3/8 in. (27 × 18.7 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

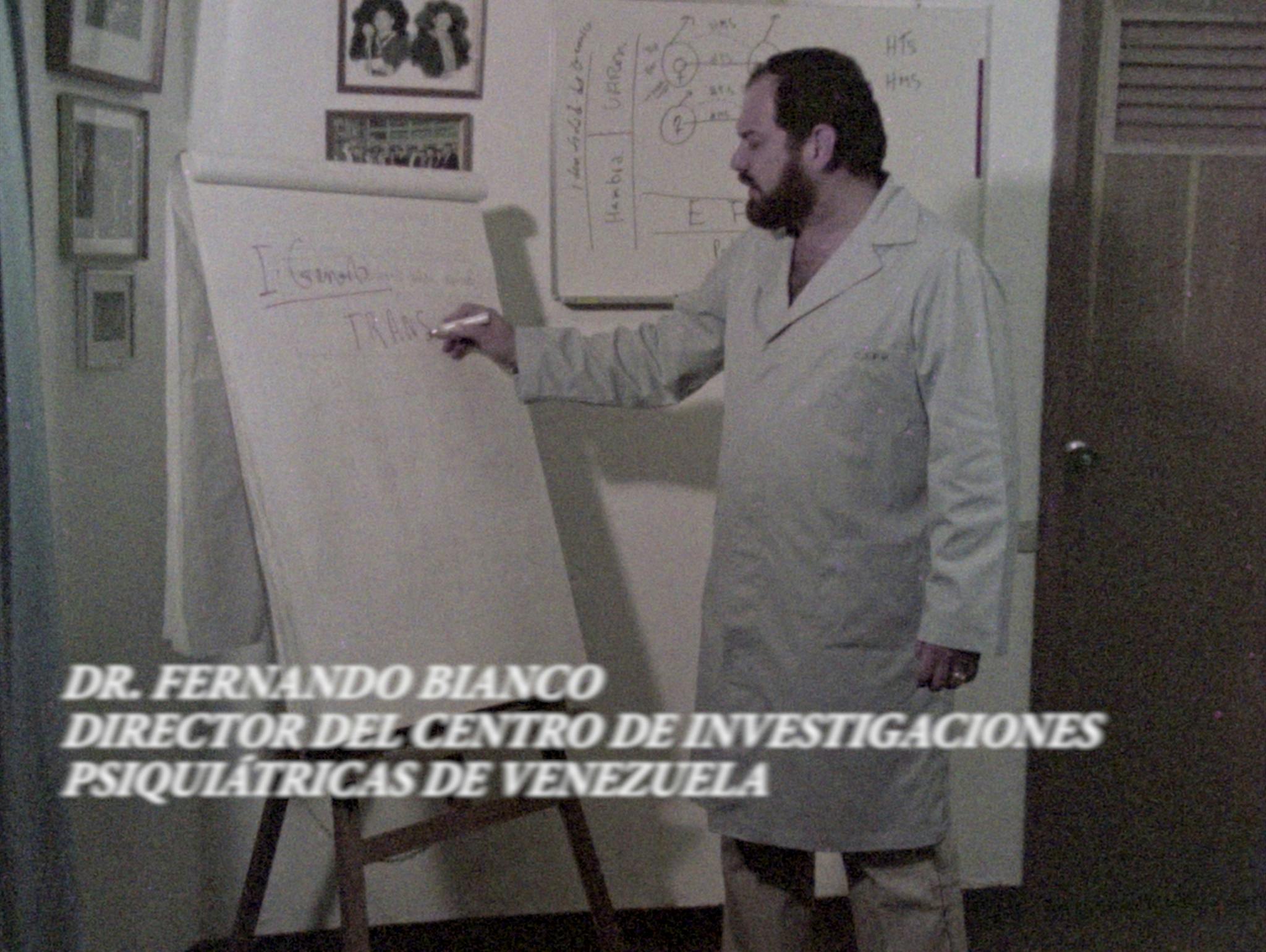

Manuel Herreros de Lemos and Mateo Manaure Arilla, Trans, 1982 (still). 16mm film transferred to video, sound, 22:05 min. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

Manuel Herreros de Lemos and Mateo Manaure Arilla, Trans, 1982 (still). 16mm film transferred to video, sound, 22:05 min. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

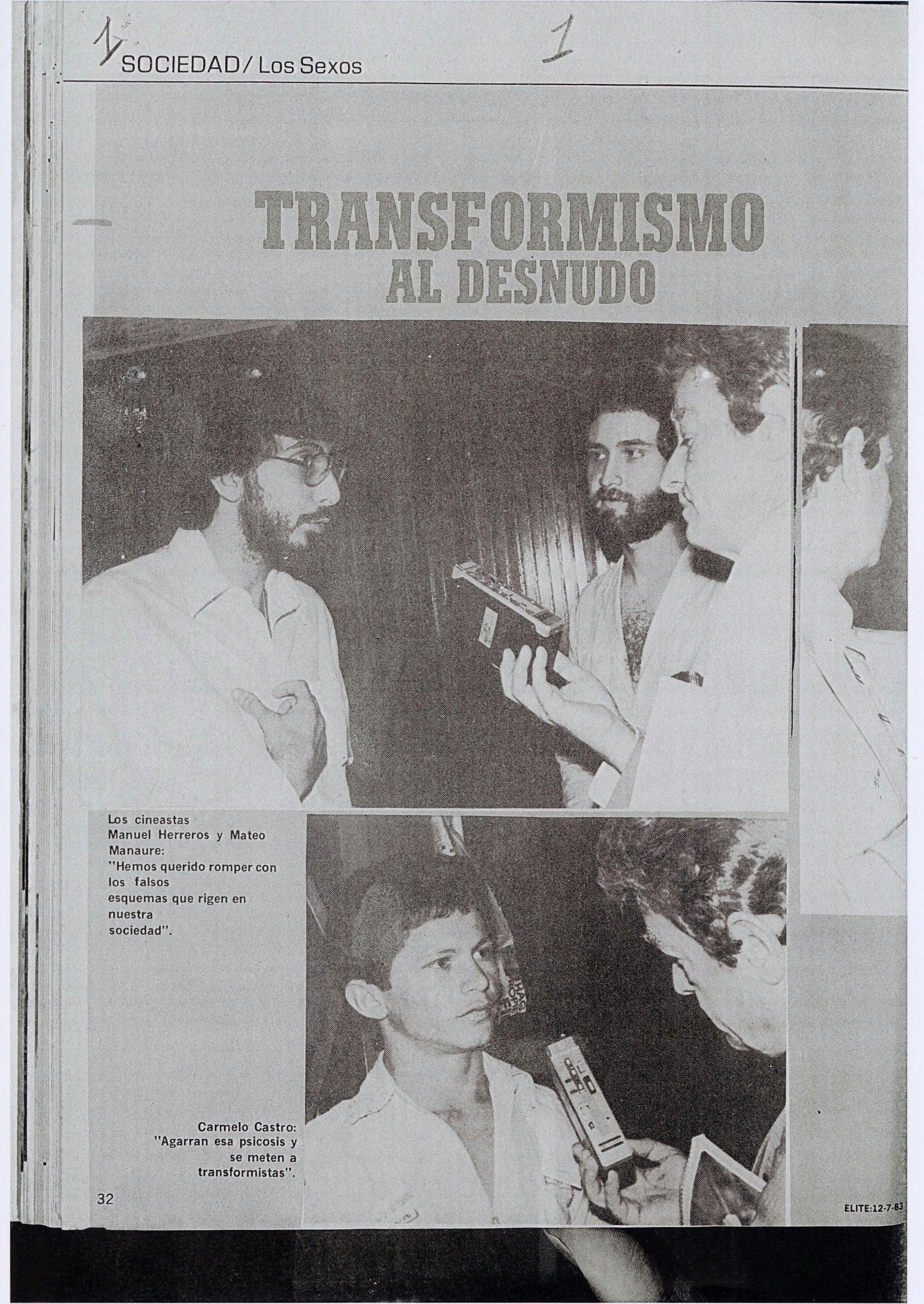

German Hauser, “Transformismo al desnudo,” Élite: La revista venezolana, July 12, 1983. Photographs by Victorino Aguilar. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. Courtesy Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

The Writer in Residence series offers scholars the opportunity to conduct research on Latin American art through materials in the ISLAA Library and Archives.

She fills the screen like an ember: glowing, feverish, uncontained. Before introducing herself by name, Venezuela, one of a handful of women who feature in the documentary short film Trans (1982, directed by Manuel Herreros de Lemos and Mateo Manaure Arilla), appears to the viewer performing an impassioned, lip-synced rendition of Irene Cara’s 1980 hit, “Fame.” Flooded in crimson light, she plays to the camera, vamping and twirling about the Club Sinfonía in Caracas’s Sabana Grande neighborhood. Midway through the number, she sheds a thin negligee, revealing her fur-covered pasties and thong as she writhes to the up-tempo tune. A scene of zealous delight, of stardom on the brink of collapse.

Venezuela’s cameo in Trans was, in many ways, orchestrated for her. Perusing a shot list developed during preproduction, one finds how the directors slot Venezuela, her body, and her gestures into a prearranged semiotic rubric. “While singing and dancing,” the document foretells, “she performs a striptease, revealing to us that this sensual woman . . . transforms physically, little by little, into a man.” 1

It is in the slippages between conceptualization and filming, between the archive and the final cut, that the asymmetries and incommensurabilities of Trans surface most palpably. For if the filmmakers intended for Venezuela’s act of undressing to categorically distinguish transfemininity from a cisnormative analogue, their informant evidently goes “off-script.” With her waggishly hairy nipples, cheeky strip of faux pubic hair, and refusal to unveil her body any further, Venezuela not only denies this moment of supposed “reveal,” but capsizes the fallacy of a definition of womanhood that ontologically hinges on anatomical or gynocentric determinations. There is no “transformation,” as the quasi-screenplay prophesies; only a performer arriving more fully into her flesh, burlesquing the expectations of unfemininity into which the preproduction narrative casts her.

Throughout Trans, women like Venezuela maneuver, just as they are expected to set into motion, a cinematographic and conceptual arena that visually demarcates, and imagines as a worthwhile subject of public debate, trans femme, transformista, and travesti life. 2 Not unlike the nation-state whose name she shares, Venezuela becomes a prismatic construct onto which disparate fantasies, fabrications, and failures are projected. But how did she and her costars negotiate their participation in Trans given the project’s directorial predispositions? In what moments were they able to magnify the chasm between documentary film’s feeble claims to objectivity and the uncapturable realities of their worlds, between cinema’s fleeting promise of celebrity and its simultaneous closing in on one’s personhood? And what strategies did they deploy to disarticulate this film’s attempt at adjudicating on trans presents and futures?

To approach these questions, this essay presses at the paradoxical aspirations that subtend Trans as a filmic project—tensions animated by the limits of cultural representation and liberal frameworks of queer inclusion. On one level, the documentary righteously sets out to destigmatize the lives of trans Venezuelans; and yet, its means for doing so rely on the scopic delineation of gender-variant bodies and their compound marking as errant, delinquent, and pathological. Historicizing these antinomies within late twentieth-century, albeit ongoing, models of (gender)queer assimilation, this text explores how the film’s trans subjects appear, perform, pantomime, and present themselves before the camera. I argue that these leading ladies, aware of the mainstream cultural perceptions circumscribing transness, and therefore of the ways they were bound to figure in a film such as this, deftly navigated a slate of competing demands: the promises and perils of state recognition, respectability politics, and dreams and desires transcending those made teleologically conceivable by the production.

Manuel Herreros de Lemos and Mateo Manaure Arilla, Trans, 1982 (still). 16mm film transferred to video, sound, 22:05 min. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

Manuel Herreros de Lemos and Mateo Manaure Arilla, Trans, 1982 (still). 16mm film transferred to video, sound, 22:05 min. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

Baby, look at me / And tell me what you see

Venezuela is but one of the women who lend their voices and likenesses to Trans. In a group of on-camera interviews, trans caraqueñas relate their experiences of dysphoria, exclusion, and femme self-becoming; they are joined by vignettes in which trans women ready themselves, mosey about Caracas, and work the city’s streets, from meeting clientele to a filmed arrest. While these scenes are those in which the present text is most invested, they form a fraction of the film’s overall footage. In reality, Trans intersperses its portrayals of trans life with commentary from invited interlopers; these include a psychiatric doctor, police official, and Catholic priest, as well as unsuspecting passersby across sidewalks and city squares.

The filmmakers invite a chorus of opinions into the documentary, positing trans existence as a topic of worthwhile debate. As one promotional handbill professes, this choice was designed to present trans Venezuelans “in the context of a macho and feminist society that marginalizes and humiliates them,” epitomized by “the reactionary attitudes from repressive sectors of the State.“ 3 In a few moments, the film goes so far as to express its repudiation editorially: during the clips in which the religious and police spokespeople spell out their views of trans unbelonging, the audio of their monologues decrescendos, replaced by the swelling sounds of chamber music and a playful symphonic overture, respectively. Their beliefs on the matter, Trans farcically argues, add little to this conversation.

Yet this sonic strategy does little to upend the disputation of trans validity that the film intends to critique; instead, it further choreographs the idea of gender-variant embodiment as a contested existence. “It’s a physically unbalanced person,” parrots a child interviewed in the documentary. “They’ve lost a part of humanity,” follows an off-the-cuff patrolman. The attitudes that the production cements in celluloid, together with its tongue-in-cheek silencing of certain factions, call forth the (re)articulation of viewpoints that refuse trans personhood—including, we find, among moviegoers exiting the Cinemateca Nacional after the film’s premiere in 1983. 4 In a feature published in Élite: La revista venezolana, audience members form their own personal juries to tackle the “question” of trans life. The first quoted individual, a twenty-one-year-old security guard, plainly declares that these are “sick people: they catch ahold of that psychosis and become transformistas.” 5 If Trans attempted to capture the prejudices that envelop genderqueer embodiment, its on-screen rehearsal of a court of public opinion also stretched beyond the cinema, sustaining the false premise that the possibilities of trans life may be left to the conceits and consensus of others.

The documentary’s contradictory ambitions are further illustrated by its preselection of the reverend, doctor, and police general to appear on camera. According to the abovementioned shot list, these representative voices “[address] three key themes, which are the religious, the scientific, and the legal,” weighing in on such topics as “the aspects [of trans life] that collide with the norms established by the Church” and “whether or not [trans people] are sick, as many people consider.” 6 The film reproduces, rather than reattributes, the authority of a triad of institutions that have, in ways both historic and ongoing, explicated transness in pathologizing terms. For example, the inclusion of a psychiatric doctor-cum-sexologist abets the twentieth-century medicalization of trans embodiment—a process whose “signature effect,” as writes historian Jules Gill-Peterson, “has been to restrict trans life to a singular definition while simultaneously placing an etiological question mark upon trans people.” 7 A similar question mark haunts the on-camera testimonies, deferring the fate and presentness of trans personhood to a matter of continued debate. Much as its interrogatory inflection casts a shadow of doubt over trans self-determination, so too does it compromise the documentary’s ability to negotiate the demands and horizons of trans being.

Production still from Trans, 1982. Inkjet print on Hahnemühle paper, 10 5/8 × 7 3/8 in. (27 × 18.7 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

Production still from Trans, 1982. Inkjet print and pigment on Hahnemühle paper, 10 5/8 × 7 3/8 in. (27 × 18.7 cm).Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

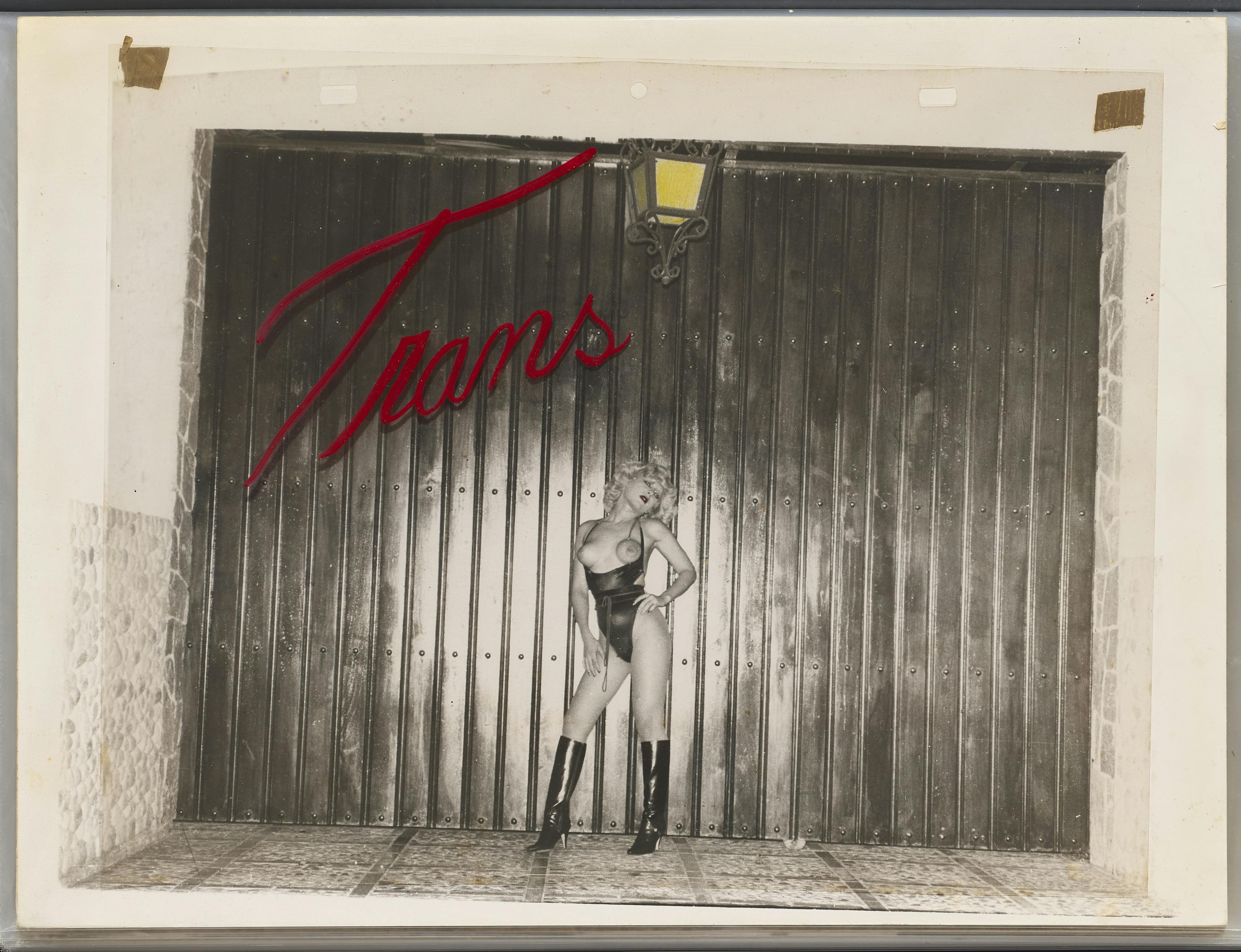

Title card from Trans featuring Marilin, 1982. Inkjet print and pigment on Hahnemühle paper, 10 5/8 × 7 3/8 in. (27 × 18.7 cm). Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

Manuel Herreros de Lemos and Mateo Manaure Arilla, Trans, 1982 (still). 16mm film transferred to video, sound, 22:05 min. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

I’m gonna make it to heaven / Light up the sky like a flame

When our mere presence is rendered a point of contestation, what become the thresholds of our spoken desires, the potentialities of our demands? And when the aperture opens onto our lives, even if for a few moments, what do we stress, conceal, vocalize, and defend? Outside of Venezuela’s arguably pre-scripted scene, other women appear in the documentary more spontaneously, eluding mention in the film’s planning documents. Regardless of their knowledge of the exactitudes of Trans, these protagonists evidently present themselves—by way of their appearance, postures, and words—in ways that counter the commonplace, vilifying depiction of trans subjects in popular media of the time. Strikingly, they downplay questions of difference or the possibility of a coalitionist politics to shape their fifteen minutes (or more precisely, seconds) of fame.

In the first of these monologues, which abruptly follows the priest’s drowned out homily, an anonymous trans woman perches elegantly on the hood of a car. A fixed shot frames her body against a pleasant residential neighborhood; her long-sleeved floral dress and tasteful jewelry position her as well suited to this backdrop of genteel life. Her speech is as earnest as it is pellucid:

"I’m not a person who has two heads or three hands or two . . . four eyes or anything. I pass beside people and they get scared upon seeing me. And all because I’m a transformista. But why does this frighten people? You understand? Why? If it’s a normal thing, if I bear the attributes of a woman, if I have the breasts of a woman, I have a body of a woman . . . how am I going to put on men’s pants? Don’t you think that would be more ridiculous? That would be more ridiculous. So, I have to dress in alignment with how I feel, because I feel like a woman, you understand? I never feel like a man."

A vision of acceptance and unremarkability, one made possible within a limited economy of “passing,” animates her entreaty. In rhetorically advocating for her own womanhood, she smartly plays into the social hyperfixation on trans anatomy, evident in adjacent commentaries in the film, to suture transness to a then-familiar paradigm of femininity.

The film cuts to a long shot of this woman among her friends, one of whom is the next to make her case before the camera. She stands before a stone wall from which juts a slatted fence, its clean white hue and encroaching foliage visually rhyming with the trope of middle-class, white-picket-fence domesticity. Very few pauses separate her sentences; it’s as if she were trying to outpace the splicing of footage that will inevitably curtail her words:

"I go out walking on the streets and downtown, and people look at me because I draw a lot of attention. But I can’t walk by a corner where there are many people because, right away, I get called 'transformista;' I get called 'man;' I get called a lot of unpleasant things . . . But here [in Caracas], human rights should be upheld. We’re all human. We all have the mental capacity to be able to walk on the streets, to be respected. Look, yesterday, today, they buried one of our friends—beaten, run over. Look, if that were to happen to me, how would that be?"

Across these two clips, the women make appeals for their own humanity rooted in a liberal model of tolerance and equality. They seek to make themselves visible as political subjects—ones deserving of safety and dignity—through their similitude to the category of cisgender women and, where that fails in the eyes of the state, the whole of humankind. Notwithstanding the sincerity of their accounts, their portrayals of trans disenfranchisement and violence also operate on a tactical level. Given but a few moments to represent their experiences, and in turn, an abstract collective of genderqueer identity, the pair acquiesces to a politics of respectability—to a sanitizing of their cragginess and incongruities before a cisgender majority—in order to advocate for their very survival. They locate, through both their diction and polished images, trans belonging within a grammar of assimilation and propriety, speaking directly to a future of legal protection as state subjects. Whereas today, many trans and travesti activists in the hemisphere have insisted on their irreducibility to legible forms of belonging vis-à-vis the legislative reforms aimed at representing them, in the early 1980s, the two women in Trans envision the contours of political recognition as something at once auspicious and owed. 8

Within the conceptual and visual confines of the documentary, however, these aspirations meet a vexed terrain of possibility: where this pair voices a longing for acceptance into an existing feminine and citizenly order, Trans marks their bodies and those of women like them as always already out of step, out of line, and out of place. B-roll footage and edited montages spectacularize the presence of trans subjects in everyday life. The camera lingers over each movement as one starlet rolls pantyhose up her legs, applies makeup, and brushes out her blonde curls in the privacy of her bedroom. It assiduously scans the body of another woman seated at a hair salon—camerawork in stark contrast to the wide pan shots of a presumably cisgender clientele that precede it. 9 Even the movie’s title card functions in a similar manner, floating a luminescent, handwritten “Trans” atop the fabulous likeness of somebody whose own desired means of being seen this fragmentary label overwrites.

If there is one site where Trans most insistently locates, and thus defines, its subjects, it is along the Avenida Libertador, a main thoroughfare of Caracas, which is presented as a stage for sexual labor and confrontations between trans femme glamor and male desire. As cultural anthropologist Marcia Ochoa has argued, “transformista visibility is inextricably tied to the practice of sex work on Avenida Libertador.” 10 During their research for the film, the crew produced a striking group of eighty-seven photographic stills taken on and near this street, attesting to its centrality in their early conceptualization of the project. 11 The first minutes of the documentary largely focus on this stretch of road, as their subjects, backlit by the glaring headlights of passing traffic, gather, pace, seduce, and solicit along its shoulder. In the final quarter of the film, we witness a mob of police officers chase a group of women before detaining them in a paddy wagon. It is a scene with a tinge of artifice: the women “flee” in the direct paths of the patrolmen, some submitting willingly to their own arrests, and are recorded from multiple, coordinated angles; a voiceover of the police general serves as a reminder of this sector’s cooperation in the project. This seemingly dramatized event construes the deep-seated criminalization of transness and sex work as both a captivating spectacle and rampant inevitability.

One conservative critic of the film called forth the contradictory ways in which the footage operates: “The documentary . . . is trapped between the intention of shaking off certain prejudices and the perversity of some sordid images that do little to reinforce tolerance.” 12 Establishing its aims within an idiom of humanization and assimilation, Trans struggles to reconcile its egalitarian motives with the politics of looking, detection, and respectability that delimit trans life and its potentialities. To participate in the film’s making, as several trans women were asked to do, thus presented a narrow frame of possibility—one in which they might attempt to garner sympathy, all while stopping short of demanding solidarity.

Manuel Herreros de Lemos and Mateo Manaure Arilla, Trans, 1982 (still). 16mm film transferred to video, sound, 22:05 min. Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) Library and Archives. © Manuel R. Herreros de Lemos

I’m gonna live forever / Baby, remember my name

The layered tensions that permeate Trans—from its devising of select scenes and cinematographic strategies of bodily demarcation to its looming deferral of trans embodiment—echo the very insufficiencies that, as numerous scholars and activists have expressed, characterize drives toward trans visibility. This neoliberal impulse of “representational justice,” in the words of philosopher Luce deLire, “forgets that the problem is not representation itself but the violence that emanates from it.” 13 To envision the on-screen portrayal of trans life as a mediative tool for social inclusion, then, disregards the exploitations and necropolitical realities that lie, and are even catalyzed, in its wake.

But in the film’s closing moments, we glimpse a set of queer and representational politics all but absent in the preceding frames. The sequence animates a “dream” narrated by Venezuela, now seated at the bar of the Club Sinfonía in a gold lamé outfit. “How I would love right now,” she muses, “to be in the fountain at the Plaza Venezuela . . . and to show up beautiful, as I am. Gorgeous, striking. Transformista!” She proffers this fantasy as a symbolic farewell before decamping to Europe where, she explains, she feels she can achieve her goal: “to be a complete woman, so that people respect me as I am.” A sketch of this soliloquy appears in the preproduction shot list, raising questions yet again as to its origins and those of Venezuela’s simultaneous valorization of transformista euphoria and cis feminine alikeness.

The documentary then cuts to Plaza Venezuela’s imposing fountain, alight in green and red hues against the inky darkness of the capital, as Billo’s Caracas Boys’ recording of the rhythmic merengue “Abusadora” begins to play. 14 Little by little, cars pull up to the fountain, dropping off some twelve or thirteen caraqueñas. Venezuela is the first to march up confidently to its perimeter, tossing a “do not enter” sign that blocks her way. Her comrades follow closely behind. They stride toward the water hand in hand, wade through its shallow depth, and climb to the structure’s apex; once there, they strike poses, romp, and outshine the vista surrounding them.

It is an assemblage of self-assured defiance, of reverie turned actuality, of reclamation and disobedient belonging. The scene veers from the original narrative dictated in the shot list, which “scripts” the oncoming blare of police sirens—a threat that, in the final cut, never arrives. Instead, the women’s shadowy, silhouetted debauchery takes hold of public space and the denouement of a film that, throughout, has paradoxically questioned their inhabitation of it. They teeter playfully on the edge of visibility, virtue, and a concern for how they are outwardly perceived, infiltrating Trans with a filmic and political agitation that exceeds the project’s portrayal of them.

The credits begin to roll. In their final frame, the filmmakers thank “especially all the trans [women] of Caracas.” And as the lights of the theater come back up, one is left to wonder if these words rang meaningfully, hollow, or somewhere in between for those subjectified on the silver screen.